Extreme-Tic-Tac-Toe

Tic Tac Toe – featuring the classic game and a new mode where you can choose the size of the board.

Why it exists

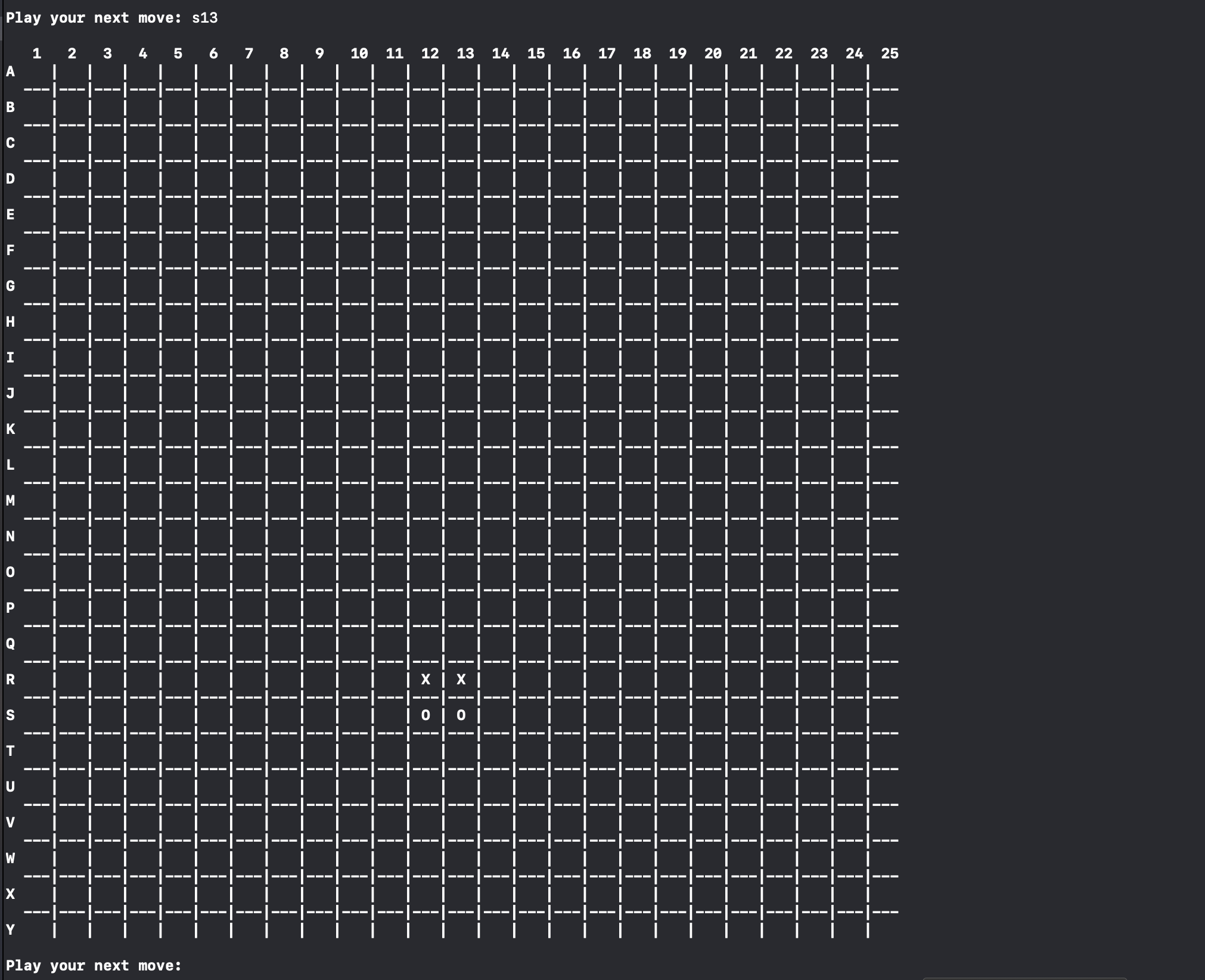

This project features two versions of the game: 1) the normal version everyone played growing up, and 2) a new version that allows players to determine the size of the board. In the normal version, you can win the game as expected: get three in a row on the horizontal, diagonal, or vertical. In the new version, however, the number of pieces you get in a row is dependent on the size of the board. Consequently, if the size of the board is 25 (the maximum size), a player must have 25 of their pieces in a row to win the game.

While there is certainly not any good reason to play a 25x25 game of tic-tac-toe, it is the theory behind the game that makes it compelling as a project. As the size of the board increases, the number of squares on the board increases exponentially. In the class game the size of the board is ‘3’ – 3x3 = 9 total squares on the board. In a game that uses the max board size, 25x25, there is a total of 625 spaces on the board.

Computationally speaking, as the size of the board increases it becomes more and more expensive to check all of the spaces for a winner. Checking 9 spaces is no problem, but checking 625 spaces every turn is not only inefficient, but is completely unneccessary. For the new version of the game, a new system had to be devised to elegantly check for a game-winner without taking too much time, or being computationally expensive.

For most computers, 625 iterations does not take long, but if this game were to be scaled to a board that was 100x100, 1000x1000, or larger, it would become increasingly necessary to be able to determine if a player won without checking every space on the board. This project is not only fun to play with, but it is also interesting as a study in algorithm optimization.

How it works

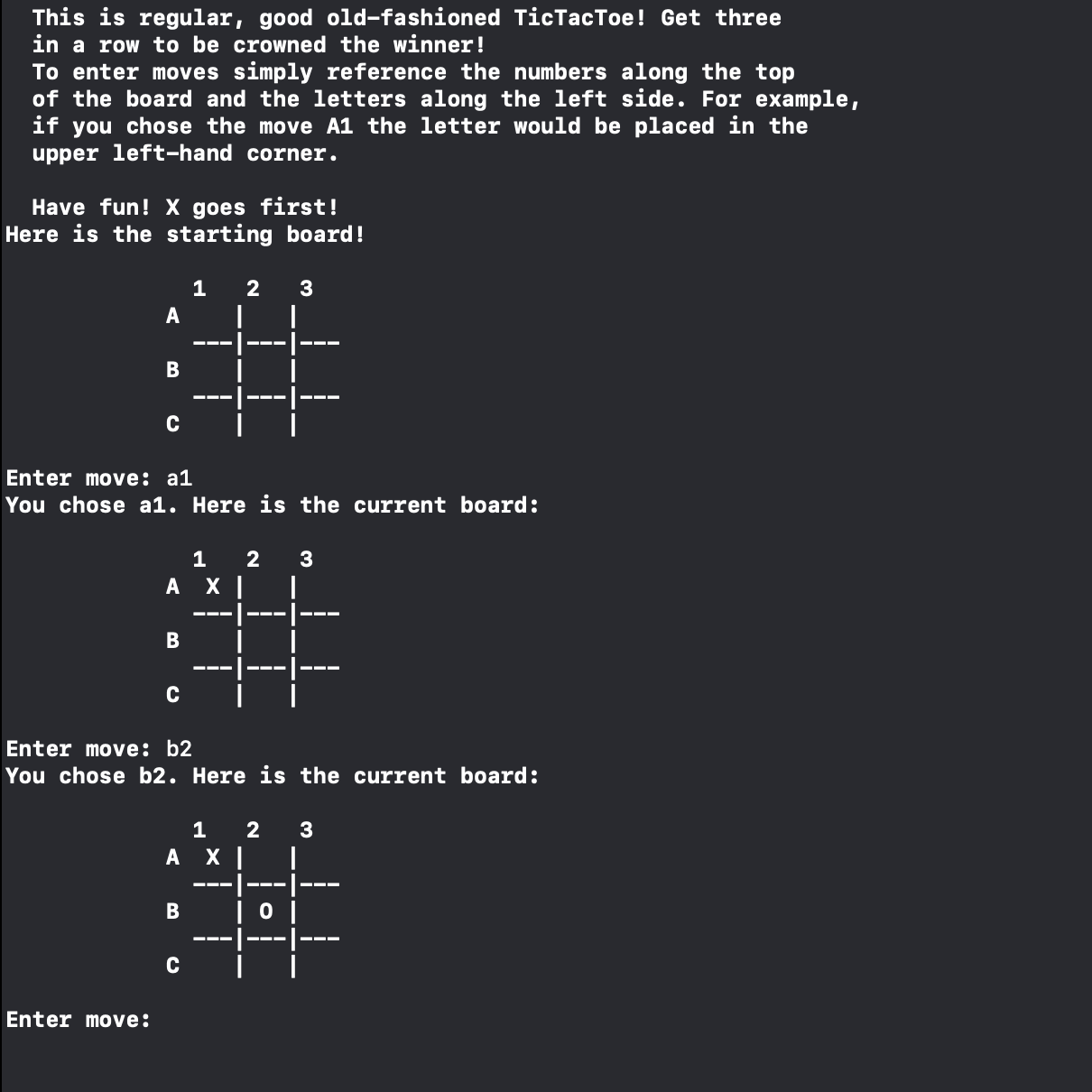

The normal version of this game is very simple. All of the spaces on the board, the board design, how long the game lasts, and other elements are hard-coded because none of the values change for this version of the game. The game cannot last more than 9 moves, it will always result in a winner or a tie, and there is only 9 spots on the board.

The spots on the board are represented by a dictionary, where the keys are the spots on the board, and the values are the existing pieces in those spots. Since every game starts with an empty board, all values start as empty strings.

var spots = ["A1": " ", "A2": " ", "A3": " ", "B1": " ","B2": " ","B3": " ","C1": " ","C2": " ", "C3": " "]

Every round a move is accepted as input from the user in the form of the dictionary keys: A1, B2, C1, etc. If a spot is full or that spot doesn’t exist, the player gets to choose a different spot. The game automatically rotates between X’s and O’s for the pieces, with the game always starting with X as the first piece.

func moveDecider(nextMove: String, currentBoard: String) {

print("You chose \(nextMove). Here is the current board: ")

print()

var next = nextMove

next = nextMove.uppercased()

currentLetter = currentLetterCounter % 2 > 0 ? "O" : "X"

currentLetterCounter += 1

spots.updateValue(currentLetter, forKey: "\(next)")

}

func letterPlacer(nextMove: String, currentBoard: String) -> Int {

let next = nextMove.uppercased()

if (spots["\(next)"] == " ") {

moveDecider(nextMove: nextMove, currentBoard: currentBoard)

return 0

} else {

print("Spot is already full! Pick Again!")

return 1

}

}

The normal version of the game is easily won, and it is also trivial to determine if the game has been won. In order to check for a winner all that is necessary is to loop through the 9 spaces on the board and check for 3 in a row of either type of piece. Given that there is only 9 spaces to check, doing this is very quick and can be done every turn in a negligible amount of time.

Similar to the normal version of the game, the new version of the game also uses a dictionary to store the spots on the board and the existing pieces on the board. Something that is different, however, is that because the size of the board in the new version is unknown, a board has to be automatically generated for every new game that is played.

//creates a dictionary of the given size for each spot on the board

func createDictionary(size: Int) -> Dictionary<String, String> {

var spots = [String : String]()

for i in 0..<size {

let currentLetter = Int(("A" as UnicodeScalar).value)

let key = ("\(Character(UnicodeScalar(i + currentLetter)!))")

for i in 1...size {

spots.updateValue(" ", forKey: "\(key)\(i)")

}

}

return spots

}

This is mostly accomplished by the above code which populates the dictionary with the correct spaces that would be in a board with the given size. The above code uses the given size as a parameter and then generates all of the ASCII characters that would be included, ties them together with an integer, converts the space to a string, and then inserts that new space into the dictionary. The game is determined to be over when either the entire board is full, or a winner has been found.

Optimizing win-checking

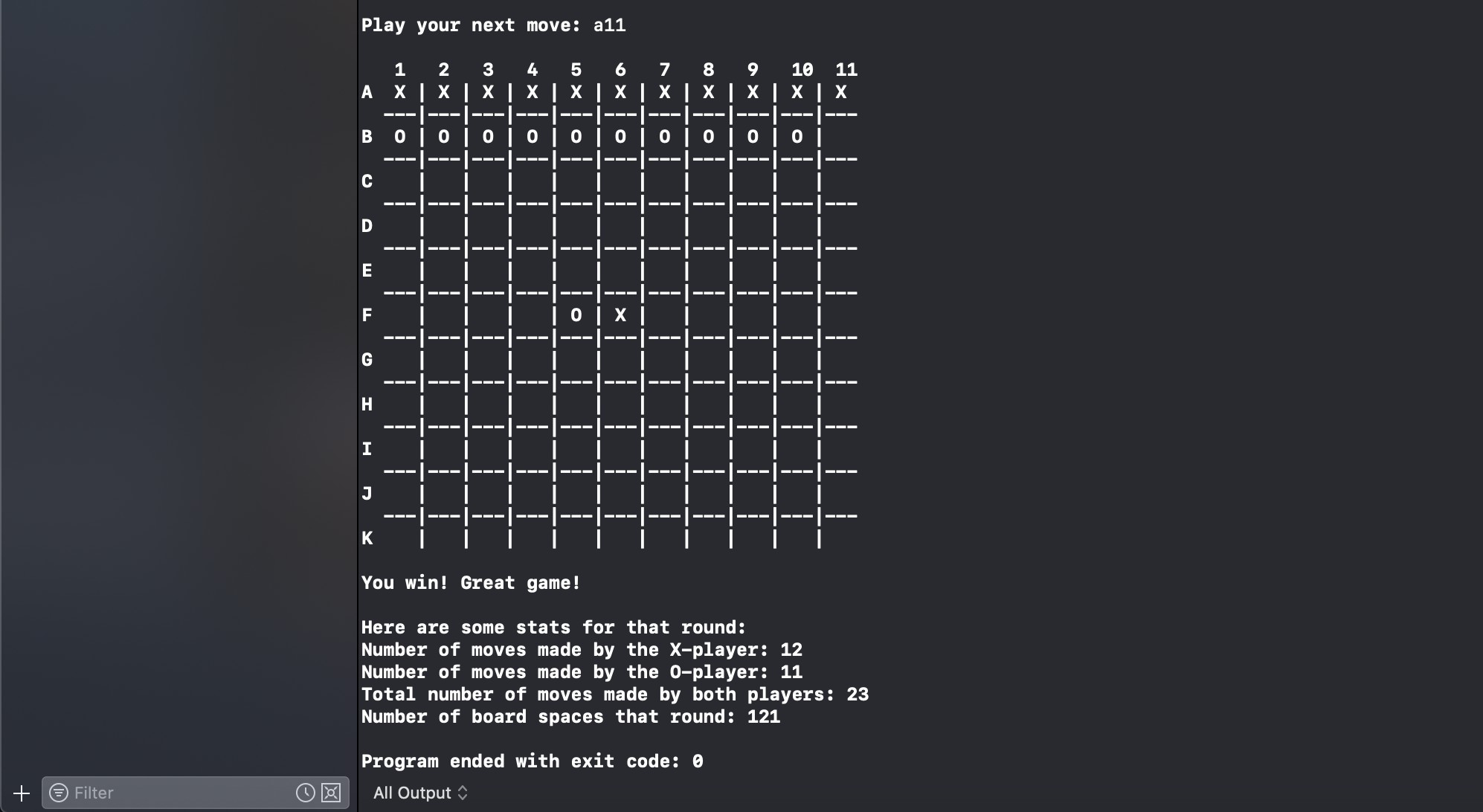

An unoptimized, brute-force solution to determining if there has been a winner is to check every column, every row, and the longest diagonal for an uninterrupted stream of the same piece. This, however, is an incredibly poor algorithm choice for determining a game winner. Not only are you checking rows, columns, and spaces that might not even have pieces in them, you are also checking spaces that might not have a shred of relevance to the previous move that was made.

This gives us a runtime that is O(n^2 + n) or just O(n^2) where ‘n’ is the size of the given board – in other words, we are left with an exponential time complexity that does not scale well with larger games.

It does not make sense to check spaces that are nowhere near the previous move, this is just wasted time. It also does not make sense to check a diagonal unless it is on one of the long diagonals. Further, it does not make sense to check for a winner at all unless the number of played pieces equals twice the size of the board - 1. If a 25x25 board is being played on, in this scenario, it is impossible for a winner to exist until a minimum of 49 moves have been played (25 - X, 24 - O).

Considering this information, a new optimization strategy can be approached as follows:

- Only check for a winner if the number of moves equals at least 2x the board size - 1

- 25x25 = 49 moves, 100x100 = 199

- Only check for a winner on a space that was just played

- It does not make sense to check random spaces on the board

- If an opposing piece is found on a row, column, or diagonal the search should be immediately aborted

- Winning requires an uninterrupted stream of the same piece type

- If a piece is not on the longest diagonal, checking the diagonal can be skipped entirely.

- In fact, once one of each type of piece have been played on the diagonal, it never has to be checked again. Winning on that diagonal will be impossible.

Using this information, a brand new algorithm can be created. This algorithm only checks the row, column, and diagonal – if necessary – of the space that was just played, and only after (2 * board_size) - 1 moves have been made.

If we wanted to optimize this solution even further we could create two auxiliary arrays that store integers. One array would represent the columns on the board, and the other array would represent the rows. When a row or column on the board becomes full, only then would the algorithm be allowed to check for a winner on that row or column. Every time a move is made on the board, its corresponding index in the row array and column array would be incremented until it reached the size of the board, at which point it could finally be checked for a winning combination of pieces.

Using this auxiliary storage, which takes at most O(k) memory – where k is the size of the board – the algorithm could easily be prevented from doing unnecessary checks for winning moves which would drastically improve the performance. The final iteration of this algorithm produces worst case time complexity of O(n), but on average actually performs much better because it will only have to check for wins once the board starts to become full.

How to play

As long as you have a Mac and Xcode, it is incredibly simple to try this project out:

- Download the zip file for this project

- Open up the file in Xcode

- Build the project

- Click ‘run’ and it should be good to go!

Note: The game will tell you how to play, but to play regular tic-tac-toe enter 1 and to play the new version enter 2.